Special thanks to Ray Robinson and Jeff White for sharing this week's script from Wavescan. Another not-to-be-missed edition.

Jeff: From 1952-1964, the U.S. Information Agency operated a Voice of America station from on board the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter ‘Courier’, anchored off the island of Rhodes, Greece. It was equipped with a 35 kW shortwave transmitter and a 150 kW medium wave transmitter – the most powerful that has ever been installed on a ship. Perhaps inspired by this, as well as by numerous other offshore stations that were by then operating in European waters, the BBC in London announced in 1965 that they too planned to establish a radio station on board a ship. Ray Robinson has the story.

Ray: Thanks, Jeff. Well, this all has to do with the political situation in the country of Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, in the mid-1960s. So to understand that, we need briefly to review some history.

In the year 1888, mining rights were granted by the Matabele people to Cecil Rhodes, a prominent Englishman living in South Africa. Seven years later, the Matabele territory was named Rhodesia in honor of its founder, though ten years later again (in 1905), the U.K. divided the territory in two - Northern Rhodesia and Southern Rhodesia. Beginning in the late 1940’s and throughout the 1950’s, the U.K. began a policy of granting independence to many of the colonies worldwide that had previously been part of the British Empire, usually establishing democratic forms of government, with voting rights for all citizens, the same as in the U.K.

In 1964, Northern Rhodesia was granted independence as the nation of Zambia under their first president, Dr. Kenneth Kaunda. The tribal situation in Northern Rhodesia was very fractured, with many small ethnic groups and over 40 different languages being spoken. Dr. Kaunda was able to unify the country, with English being taught and used exclusively in secondary education, and for trade and government. The country was rich in natural resources, principally copper, and although it has faced its challenges and has been plagued by

corruption, on the whole it has become one of the most stable democracies in Africa.

However, in Southern Rhodesia, which after 1963 just used the name Rhodesia, the situation was quite different. The population there included a sizeable minority of white people, many of whom were land-owning farmers, mostly English-speaking, and also some Afrikaners. There were only two main tribal groupings, and the Soviet Union gleefully exploited this, by providing financial backing for two African nationalist so-called ‘liberation movements’ – the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (known as ZAPU – the Ndebele people in the west led by Joshua Nkomo) and the Zimbabwe African National Union (known as ZANU – the Shona people in the east led by Robert Mugabe). Both were Marxist-Leninist organizations.

Under the extraordinary circumstances and facing down a likely civil war, the ruling Rhodesian Front Party led by Mr. Ian Smith decided they needed to control the propaganda narrative, and in order to do that, on January 1st 1965, they introduced limited censorship of broadcast news and the press. The Rhodesia Broadcasting Corporation (RBC) immediately dropped the relay of the morning world news bulletin from the BBC World Service, and replaced it with a bulletin from the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC). However, the afternoon and evening news relays of the BBC remained unchanged on all the RBC’s national network of medium wave and shortwave transmitters.

Nevertheless, both the BBC and Harold Wilson’s Labour government in London were concerned about the censorship, and in June 1965 the BBC announced that they were investigating the possibility of utilizing a large ship as a relay station for radio coverage into East Africa. The ship they were looking at was a redundant aircraft carrier, HMS “Leviathan”, which had been built in Tyneside, England during the latter part of World War 2. It was launched on June 7, 1945, just as World War 2 was coming to an end, and the need for the ship had passed. As such, it was never fully completed and simply lay around awaiting its destiny. It would have been incredibly expensive to crew and operate just as a radio ship, but the suggestion was to have it stationed in the Mozambique Channel near the port of Beira, with coverage for the BBC into both Rhodesia and South Africa.

Now, the Rhodesian capital of Salisbury (present day Harare) is 284 miles from Beira – on the nearest part of the Mozambique Channel - so transmissions would probably have been on tropical band shortwave during the daytime, and high-power medium wave at night. However, this radio project never got beyond the planning stages, and instead was replaced by plans for a land-based relay station in Bechuanaland. Two years later, the empty and uncompleted aircraft carrier “Leviathan” itself was sold and scrapped.

Throughout 1965, Ian Smith and the Rhodesian Front received increasing pressure from London. They resisted because of the violent unrest and inter-tribal rivalries that had already started to play out, and which they feared would escalate dramatically if Britain granted independence to Rhodesia using the black majority rule model. So, to head that off, in November 1965, the Rhodesian Front surprised and upset London by making a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (or, UDI).

In response, the British government denounced UDI as illegal, and sped up the plans for the new relay transmission facility. A temporary site had been chosen just outside Francistown in the neighbouring Bechuanaland Protectorate – ‘temporary’ because

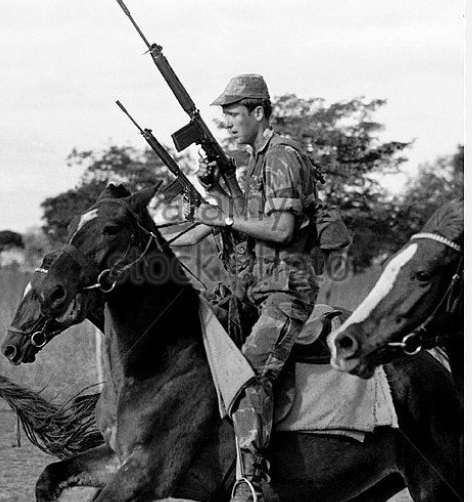

(photo via Alarmy)

Bechuanaland, now Botswana, was also in the process of its own independence negotiations. The region around Francistown can at times go for several years without rainfall, and so the almost barren 100-acre property was relatively easy to obtain quickly, and it was ideally situated just 16 miles across the southwest border from Rhodesia and 99 miles from the provincial city of Bulawayo, although the capital city, Salisbury, was some 326 miles distant.

The choice of the Francistown site did attract some local opposition protests, but on December 9th, 1965, a statement was made in the UK House of Commons that the Bechuanaland police were helping with the security of the site, and that prison labour had been used to clear it.

A quick search had been made for available transmitters and it was decided to purchase two 50 kW medium wave units from Continental in Dallas, Texas. It so happened that at the time, Continental already had several 50 kW medium wave transmitters under construction. All were model 317C’s, for various clients, one of whom was Ronan O'Rahilly, the founder and operator of the British offshore station ‘Radio Caroline.’

The ship used by Radio Caroline South, the MV Mi Amigo, had initially been converted to a radio ship for the Swedish offshore station Radio Nord in 1960. Being anchored in International Waters about 20 miles from the capital Stockholm on the Baltic coast, only a 10 kW transmitter had been necessary to cover the city with a good signal. But when the ship was moved down to a new anchorage in the southern North Sea in 1964, it was more like 60 miles from central London, where the 10 kW signal was marginal in some areas and didn’t penetrate buildings all that well. Then in late 1964, a competitor offshore station had arrived in the form of Radio London with a much more powerful 50 kW transmitter that covered London and south east England far better. Thus, in 1965 Ronan had decided he needed to upgrade the transmitter, and had placed the order with Continental.

When approached by the British Foreign and Commonwealth Office, in an act of goodwill, he agreed to allow them to take the Continental 50 kW medium wave transmitter, model 317C, no. 12 that he had ordered. This was then flown direct from Texas to Francistown and installed in what became the new Central Africa Relay Station. The next Continental transmitter, no. 13, was similarly diverted and installed in Francistown shortly afterwards.

Interestingly, O’Rahilly then took transmitter no. 14 for Radio Caroline and it was installed on board the ‘Mi Amigo’ in February 1966 during a refit at Zaandam in The Netherlands. When the ‘Mi Amigo’ finally sank in March 1980, the two transmitters on board – the original 10 kW and the Continental 50 kW – both went down also. They are still there to this day, on the bottom of the shallow waters of the North Sea!

But, I digress! The Central Africa Relay Station was quickly constructed under the supervision of Harold Robin who previously had also supervised the installation of the American high-powered medium wave transmitter ‘Aspidistra’ at Crowborough, Sussex, England during World War 2. A total of 60 tons of radio equipment was flown from the United States and England for installation at Francistown, and 18 British technicians installed the equipment. As well as the two medium wave transmitters from Continental, two 10 kW Marconi shortwave units had been sourced from the UK.

The first medium wave transmitter and the first shortwave unit were inaugurated on December 30, 1965. The second medium wave transmitter and the other shortwave unit were inaugurated a few weeks later, early in the New Year of 1966. The medium wave transmitters were then operated in tandem for a combined output power of 100 kW on 908 kHz, and the shortwave transmitters were used on various frequencies in the 60 and 41 metre bands.

|

| British Diplomatic Wireless Service |

The station was not directly operated by the BBC, but rather by the British Diplomatic Wireless Service (the DWS). Programming was entirely in English; either the BBC World Service, the BBC’s other regular programs for Africa, or special content made specifically for Rhodesia. Some of the programming was pre-recorded by the BBC Transcription Service and flown to Francistown from England. Live program feeds were also taken off shortwave, both direct from Daventry and via the BBC relay station in Cyprus. At the height of its service, the Central Africa Relay Station used the four transmitters in parallel for a total of 15 hours daily.

In order to block the broadcasts from Francistown, on March 21, 1966, the Rhodesian government retaliated by activating jammers at several different locations, including Salisbury and Bulawayo. The medium wave jammer was a massive 400 kW unit, nicknamed ‘Big Bertha’. However, as an economy measure, the Rhodesian jammers were only turned on when the BBC programming was discussing the situation in Rhodesia itself. The jamming against the medium wave channel targeting Bulawayo was fairly successful, though jamming against the shortwave transmissions for the rest of the country was not so effective.

The temporary Central Africa Relay Station at Francistown, Bechuanaland was on the air for exactly 2¼ years, following which it was closed down on March 31, 1968. The two shortwave transmitters were donated to the new Radio Botswana and were re-located to the capital, Gaborone. One of the medium wave transmitters was sent to England for use by the BBC, and the other was flown to Cyprus where it was installed in the BBC relay station at Zygi.

A few QSL’s were known to be issued to verify the reception of the Central Africa Relay Station, but not many.

When the relay facility at Francistown was closed, the shortwave transmissions were transferred to the BBC Relay Station on Ascension Island in the South Atlantic.

Back to you, Jeff.