Joseph Goebbels commissioned a stylish, mass-producible radio to channel Nazi propaganda into German homes

By Allison Marsh, professor at the University of South Carolina

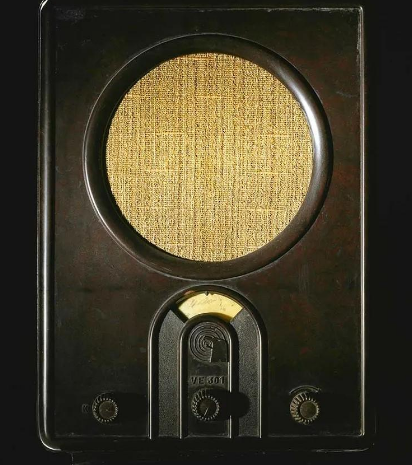

Introduced in 1933, the inexpensive Volksempfänger helped spread Nazi propaganda to an eager audience.

Jeff: Joseph Goebbels understood the art of persuasion. As propaganda minister for the Nazis, he sought to exploit radio's tremendous potential to broadcast Hitler's messages. But first he needed a way for people to tune in. Here’s Ray Robinson with the story of his ‘people’s receiver’ or ‘people’s radio’.

Ray: Thanks, Jeff. Like the story we told two weeks ago about the first transistor radio, we are again indebted to Professor Allison Marsh at the University of South Carolina for researching and documenting our story today.

Radio helped bring the Nazis to power and keep them there

On 18 August 1933, Joseph Goebbels opened the 10th International Radio Show, in Berlin, with a speech declaring “Radio as the Eighth Great Power" — a nod to Napoleon's notion that the press was the seventh great power. Goebbels argued that “the radio will be for the twentieth century what the press was for the nineteenth century." He noted the failure of the Weimar Republic to embrace radio, and claimed that the National Socialists would not have been able to take power without it.

He proclaimed: “We want a radio that reaches the people, a radio that works for the people, a radio that is an intermediary between the government and the nation, a radio that also reaches across our borders to give the world a picture of our character, our life, and our work."

Goebbels approached electrical engineer Otto Griessing to design a radio that was technically simple, easy to mass-produce, and inexpensive.

The Volksempfänger was designated model VE301, a reference to 30 January, the day in 1933 that Adolf Hitler assumed power. It was a three-tube receiver that operated in the long-wave and medium-wave bands — 150 to 350 kilohertz and 550 to 1700 kilohertz, respectively — and had a built-in magnetic loudspeaker. The radio came in three versions: The VE301 W ran on alternating current, the VE301 B was battery powered, and the VE301 G operated on direct current. The W and B sold for 76 RM, while the G was priced at 65 RM. All of the models had sockets on the left side for plugging in antennas of different lengths. A later model, the VE301 Dyn, introduced in 1938, featured an electrodynamic loudspeaker.

The Volksempfänger's radio dial was not marked with frequencies but rather listed the names of cities, such as Frankfurt and Heidelberg. [These can be seen on the model in the Deutsches Museum's Volksempfänger, pictured at top]. This made tuning into foreign broadcasts such as those from the BBC a little more challenging.

Beneath the speaker grill on the front enclosure, there was an on/off/band select knob, a volume knob, and two tuning knobs which had to be turned in tandem to acquire a new station. An ear-splitting screech could result if the receiver drifted out of tune. The Volksempfänger did have the sensitivity to pick up foreign broadcasts, but after the start of World War II in 1939, listening to them became punishable by fines, imprisonment, and even death.

Low cost was not the only reason for the Volksempfänger's popularity. The original VE301 had an attractive art deco-inspired design. Industrial designer Walter Maria Kersting fabricated the cabinet out of Bakelite, a plastic that could be easily molded. Bakelite also had insulating properties that made it ideal for the electronics industry, replacing the heavy and more expensive wood cabinetry that was then common. Unfortunately, the later VE301 Dyn lacked some of the radio's original flair. It had a rectangular speaker and tuning window, giving it a much more utilitarian aesthetic.

The government pressured 28 German radio manufacturers, including Philips, Siemens, and Telefunken, into producing the VE301. They were required to adhere to strict standards and could not alter the circuitry or housing. The only distinguishing mark they were allowed was a stamp of the company name on the

A brochure for the Volksempfänger highlights the radio's especially beautiful tone and its adherence to safety standards set by the Federation of German Electrical Engineers. Note the swastika.

back cover. A committee of experts from the radio industry, the Institute for Oscillation Research (known as the Heinrich Hertz Institute before and after Nazi control), and the Reich Broadcasting Corporation assured quality control and technical compliance. But the Volksempfänger didn't hold a total monopoly. Manufacturers were still allowed to produce other radios and to price them at market rates.

For the German people, the Volksempfänger offered welcome distraction

The original marketing materials for the VE301 made no secret of Goebbels's plan to bring radio to as many Germans as possible. One brochure claimed that, through broadcasting, the radio brought together “city and country, people and government, manual laborers and office workers, old and young."

Ads positioned the Volksempfänger as the intermediary for the greater German community that would make the country strong and prosperous again by bringing political, cultural, and economic ideas into every household. The national emblem of the eagle near the tuning dial identified the product as part of state propaganda efforts. Later models also included a swastika. An even cheaper version of the radio, the Kleinemfänger, came out in 1938 and sold for 35 Reichsmarks.

Goebbels ended his speech at the 1933 Berlin radio show with a high-minded wish: to unite science, industry, and intellectual leadership with a common goal of a “glorious German future." His success in this effort helped trigger a world war while concealing an architected program of genocide, mass murder, and oppression.

The Volksempfänger was an elegant and inexpensive piece of engineering that gave ordinary Germans access to entertainment and culture, but that sadly also became an instrument of hate. Back to you, Jeff.