|

| Gleiwitz (youtube) |

During

the mid 1930's, political events on continental Europe began to focus on

expansionism, until ultimately in 1939, it became very evident that a major war

was on the horizon. Historians tell us

that World War 2 began over the first weekend in September (1939) when massive

German air and land forces crossed the border into neighboring Poland on

several fronts.

A radio station on the edge of the

city of Gleiwitz (German) or Gliwice (Polish) featured in the events leading up

to the invasion, and this is the story of what happened.

The city of Gleiwitz was first

mentioned as a town in the year 1276, and at the time it was ruled by Silesian

dukes. Over the years, it was sometimes

part of a neighboring dukedom, and there were times when it was an independent

entity in its own rights.

In the 1300s, Gleiwitz

became a possession of the Kingdom of Bohemia, and two hundred years later it

was absorbed into the Austrian Hapsburg Empire.

Subsequently, the city was absorbed into the Prussian province of

Silesia, and in the late 1800s during the unification of Germany, Gleiwitz was

recognized with the status of a Stadtkreis, a city with its own urban district.

During the development of the

industrial era in continental Europe, Gleiwitz became a center for heavy

industries and mining. At the time,

there was strife between the German and Polish inhabitants, and under a plebiscite

administered by the League of Nations, a vote of nearly 80% ensured that the

city would remain as an integral part of Germany. However, after the end of World War 2, the

city of Gleiwitz was mandated to Poland; and this prosperous and modern city of

two million citizens remains Polish to this day.

Along with many other countries

throughout the world, the radio revolution of the 1920s was evident in Germany,

and their first radio station in Gleiwitz was inaugurated on November 15,

1925. At the time, this small station

served as a relay transmitter for the programming from the Silesian radio

station (callsign GPU) located in the neighboring city of Breslau.

This original radio station in

Gleiwitz was located on Raudener Strasse in suburban Petersdorf and it radiated

with 1½ kW

on the medium wavelength 251 meters (1195 kHz).

The aerial system was a center fed T antenna, mounted on two steel

towers standing at 245 feet high. In

1928, the power of the station was increased to 5 kW and the frequency was

adjusted to the nearby channel 1184 kHz.

Work commenced in

August 1934 on a new station on a nearby country property amidst a pine tree

forest on Tarnowitz Road, on the edge of Gleiwitz city. At the time, this location was still inside

Germany some four miles from the border with Poland.

Several new buildings were constructed,

including a new three storey transmitter building, together with a new high

self standing tower; and new electronic equipment that was manufactured by the

Lorenz, Siemens and Telefunken companies was installed.

The new tower, standing at 365 feet

high, was constructed entirely of Larch timber, a tree that is related to the

pine tree with a very durable quality.

The timbers in the high tower were fastened with more than 16,000 brass

bolts. This new radio broadcasting

station was inaugurated just before Christmas in the year 1935, on December 23,

still with 5 kW on another new though nearby channel, 1231 kHz.

Close on four years later, the

Gleiwitz radio station was suddenly and unexpectedly thrust into an ignominious

prominence as a pretext for the launching of a massive invasion of nearby

Poland. The Gleiwitz incident was one of

twenty-one provocative border incidents that occurred on that same evening, and

they were intended to create the appearance of Polish aggression against

Germany in order to justify the subsequent invasion of Poland.

As revealed in the best available

documents, this is what happened.

Shortly before 8:00 pm on the night of August 31, 1939, two cars drove

through the entrance gateway to the station and stopped outside the entrance to

the transmitter building. The small

contingent of German troops in these two cars, six men with 26 year old Major

Alfred Naujocks as their unit leader, were all clothed in Polish army

uniforms.

The

soldiers stormed the radio station building and quickly overpowered the two

security guards at the entrance doorway and the three radio engineers on

duty. Major Naujocks

fired a few shots into the air to intimidate the radio personnel, and all,

except Engineer Nawroth, were led to the basement with their hands tied.

The

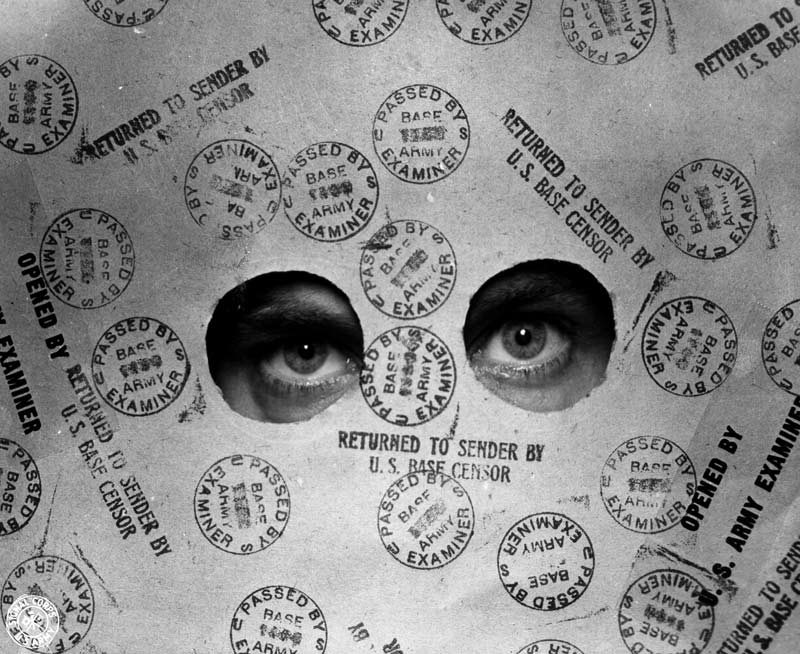

Gleiwitz radio broadcasting station was a slave relay station, carrying the

programming from the mother station in Breslau, and at the time of the

incident, a music program was on the air.

There was no production studio here in Gleiwitz, and a microphone was

inserted into the transmitter circuitry only for the broadcast of local weather

and for occasions of emergency, if needed.

Engineer Nawroth was ordered to

connect the microphone. It

is stated that they were unable to use the main transmitter and that they used

a second transmitter. This seems to be

an non-technical way of describing the use of the inserted microphone; there is

no way that a standby transmitter back then could be spliced into service so

quickly.

One of the German soldiers, Karl

Hornack, grabbed the microphone and attempted to make a clandestine broadcast

in Polish. The broadcast lasted no more

than part of a sentence before they were cut off the air by Engineer Nawroth

who surreptitiously pushed a button, effectively putting the station off the

air.

A multitude of local citizens heard

the botched broadcast, but apparently it made little impact upon them. During an interview just last year, 85 year

old Joachim Fulczyk in Gliwice recalled that he, his mother and her sister

heard the broadcast and they were puzzled as to what was happening.

On the previous day, an unmarried 43

year old Catholic farmer was arrested on suspicion of partisan sympathy with

the Poles. This man, Franciszek Honiok,

was brought by car from a local encampment to a

pre-arranged location near the station.

He had been injected with a lethal drug and was unconscious.

Honiok was shot and killed and

dragged into the doorway of the station.

There are reports that other unconscious or dead people were brought in

and shot and laid at strategic locations to indicate supposed evidence of a

Polish attack.

This raid on the radio station at

Gleiwitz was a sufficient pretext for a massive onslaught into Poland; and so

that radio broadcast was the beginning of World War 2.

And

so, what happened to them all afterwards?

Due to the realignment of

international borders after the war, Gleiwitz and the surrounding areas of

Silesia became part of Poland, and the city adopted the Polish name Gliwice.

The radio station survived the war

without damage. On October 3, 1949 the frequency

at Radio Gliwice was changed to 737 kHz, and then on March 15, 1950, the

transmitter was re-tuned to 1079 kHz. At

this stage, it was in use only as an emergency backup transmitter for the

mediumwave station at Ruda Slaska.

In

1955, this medium wave station at Gliwice was withdrawn from service, and the

facility was used for jamming Polish programming from Radio Free Europe. These days, the tower is in use for the

transmission of 50 or more mobile phone systems, and a low power FM

station. The transmitter building was

turned onto a museum in 2005, and the tower is now a tourist attraction. It is the tallest wooden tower in the world,

and the only wooden tower that is still in use for radio transmissions.

The

Polish partisan Franciszek Honiok was killed at the radio station and he was

buried in an unmarked grave, the location of which is forever unknown. He is listed officially as the first casualty

of World War II.

Major Alfred Naujocks

survived the war and he became a businessman in Hamburg Germany; he died in

1966.

We would presume that Engineer

Nawroth who put the station off the air during the surreptitious broadcast,

continued in service at the station.

Nothing more is known about the

German army

man who spoke both German and Polish, Karl Hornack; he was the temporary

announcer who made the short broadcast over Radio Gleiwitz.

Last year, (2014) 75th

anniversary celebrations of the Gleiwitz Incident were conducted at the radio

station, with representatives attending from both Germany and Poland.

And that’s

the end of the story: the radio broadcast that began World War II.

(AWR-Wavescan/NWS 340)